In our last post, we learned how steam engines were adapted to propel riverboats in Europe and the United States (if you missed that post, see Where River Cruising Began: A ‘Fire Boat’ On The Saône). In this post, we’ll look at how those boats evolved to become the driving force behind a new form of tourism: river cruising.

During the 19th century, the first steamboats began to ply the rivers of Europe and the United States. Many of these vessels were designed to carry cargo, with the transport of passengers coming as an afterthought. By the end of the century and into the 1900s, however, the boats and their voyages were starting to resemble the popular pastime that we know today: river cruises that cater annually to more than half a million vacationers.

How river cruising evolved from rudimentary side paddle-wheelers to sophisticated armadas resembling floating boutique hotels is a story that surfs waves of successes and failures. As river cruising evolved during the past two centuries to become what it is today, riverboat operators struggled against strong currents to navigate their way to success.

In our story, we’ll see how a single steamboat helped thwart an invasion of America, fought off a monopoly and then went on to open Mississippi river cruises in its wake; how steamboat companies survived two world wars that sank their boats in Europe; and how those companies survived periods of boom and bust. We’ll also learn how a well-known writer popularized river cruising in the United States and how a poet mythologized a landmark that still attracts river cruisers today.

With coal markings on her face, Alva has stoked the coal-burning furnaces that power Sweden’s S/S Blidösund for more than 15 years, a passion more than an occupation, she tells us. Built in 1910, Blidösund continues to steam along the Swedish archipelago from Stockholm. © 2013 Ralph Grizzle

While riverboats ply rivers worldwide, the majority of boats and passengers can be found on the waterways of Europe, and it is on the rivers that course through the Continent where our story takes place. But before we sail along such storied waterways as the Main and Rhine (the two rivers rhyme, by the way, with Main pronounced as Mine), we’ll go steamboatin’ along on one of the world’s mightiest rivers. It is on the Mississippi where we’ll find Robert Fulton expanding his empire of steamboats. But trouble looms as a competing company launches a paddle-wheeler set on a collision course with Fulton.

Fulton’s Folly & A Competitor That Proved Its Mettle On The Mississippi

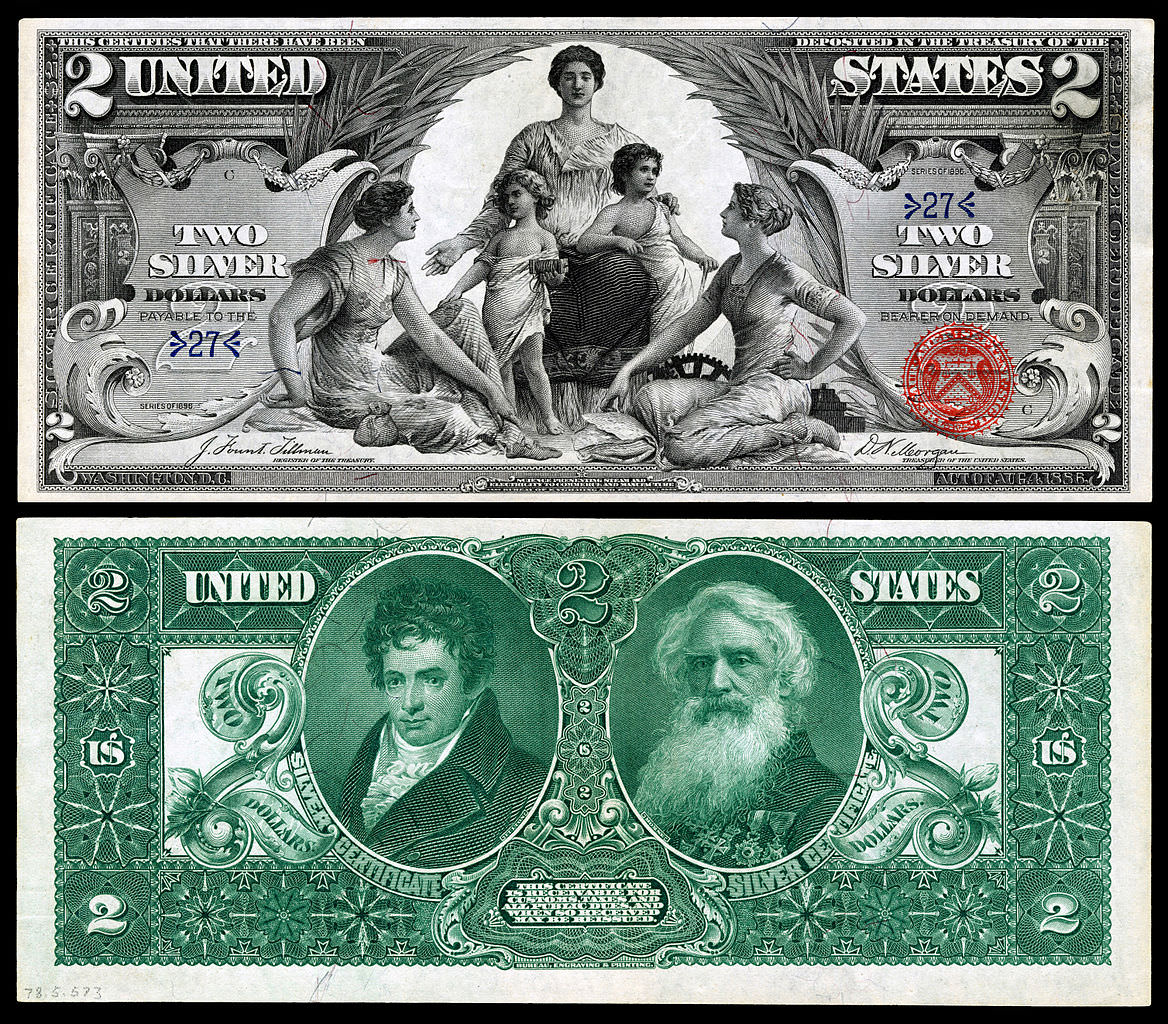

Robert Fulton (with Samuel F. B. Morse) depicted on the reverse of the 1896 $2 Silver Certificate from the United States Treasury. National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Fulton was not only a skilled engineer but also an astute businessman, or as some characterized him, a consummate opportunist. He managed not only to build steamboats but also to forge monopolies along major rivers in the eastern United States. That put Fulton at odds against steamboat builders who were eager to challenge his monopoly. How did Fulton forge these monopolies in the first place?

The story begins in the early 1800s when Fulton sunk a steamboat during a demonstration in New York Harbor. What did he receive for his failed effort? A heap of money. Congress awarded Fulton $5,000 to continue experimenting. With the funds, Fulton contracted the James Watt’s firm in England to build a steam engine that Fulton would install on a new steamboat. Flat-bottomed, square-sterned and with paddle wheels on each side, “Fulton’s Folly,” as the boat was sarcastically known, featured sleeping berths and public rooms. It was unlike anything anyone had seen before.

In August of 1807, Fulton’s new steamboat set out on its maiden voyage from New York to Albany and back. The 300-mile round trip voyage took more than 60 hours but proved the viability of transport by steamboat. The next month, Fulton put “The North River Steamboat of Clermont” into commercial service, offering one-way fares between New York and Albany for $7. The service ran flawlessly until November when ice made navigation difficult.

1909 replica of Robert Fulton’s Clermont. Photo from Wiki Commons.

Thanks to Clermont’s success, Fulton applied for, and obtained, a federal patent for his steamboat. He, along with his business partner Robert Livingston, also was granted exclusive rights to operate steamboats in New York State. Fulton next eyed the Ohio and Mississippi rivers as waterways for new commercial service. He built another side-wheeler. In 1811, New Orleans steamed from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, completing a first-ever journey on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. The side-wheeler was deep-drafted, heavy and inefficient, however, and its journey of more than 80 days was further complicated by fluctuating river levels and other hazards along the way. For his efforts this time, Louisiana awarded Fulton a monopoly to operate on the Mississippi.

Challengers to the monopolies argued that Fulton had not invented the steamboat; he has only improved on its design. As you may recall from our last post, Fulton gave credit for inventing the steamboat to Claude Dorothée Marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans, the Frenchman who successfully sailed up the Saône in 1783. While the U.S. courts affirmed Fulton’s monopoly, they had no way to enforce it – until a seminal steamboat event on the Mississippi.

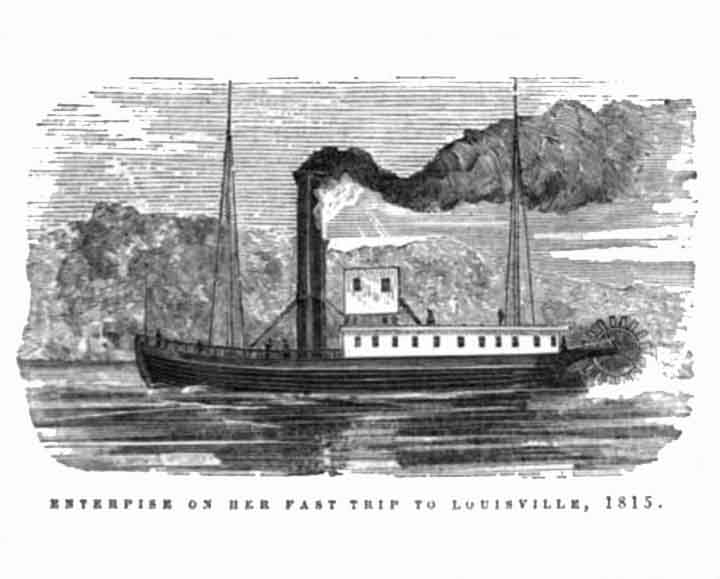

In 1814, the Monongahela and Ohio Steam Boat Company launched its new steamboat Enterprise, a stern-wheeler that greatly improved on Fulton’s side-wheeler design. In case you’re wondering, a stern-wheeler is a type of boat that features a single wheel at the boat’s rear (the stern, in nautical parlance). During its first year of operation, Enterprise transported cargo and passengers to the various ports between Brownsville, Pennsylvania and Louisville, Kentucky. The boat’s 600-mile run against the strong currents of the Ohio River was admirable, but it was a voyage provoked by the threat of British invasion where the Enterprise proved its mettle.

Between 1812 and 1815, the United States and its allies were engaged in the War of 1812 against the United Kingdom. During the winter of 1814, 60 British warships carrying more than 14,000 soldiers had amassed off the coast of New Orleans. To oppose what appeared to be an imminent military invasion, General Andrew Jackson marched troops from Mobile, Alabama to New Orleans. His effort to defeat the British was supported by warships on the Mississippi, and, yes, the Enterprise.

On December 21, 1814, Enterprise steamed out of Pittsburgh with a cargo of ammunition, reaching New Orleans on January 9, 1815. The stern-wheeler, remarkably, had made the run in just 19 days. Even with the delivery, Jackson’s forces still were in need of small firearms, gunpowder and other munitions. Jackson sent Enterprise to retrieve several boats loaded with weapons near Natchez, bringing the boats back in tow to New Orleans. Enterprise made several other trips, including one transport of 250 troops. Despite a large British advantage, the American forces handily defeated the assault with only 60 casualties, while the British lost 2,000 men.

When the War of 1812 ended, Enterprise continued to operate between Natchez and New Orleans. In early May, however, Fulton’s company submitted a petition to Federal Court accusing Enterprise’s captain and the company’s shareholders of violating Fulton’s steamboat monopoly. Though both Fulton and Livingston had recently died, the heirs of their company requested restitution in the form of payment of $5,000 and the forfeiture of the Enterprise. The captain was arrested and the ship seized. In a trial that followed, the monopoly was dissolved on the basis that the Territorial Legislature had exceeded its authority in granting the steamboat monopoly. The ruling was a win for steamboat commercial expansion and the economy of the West.

Rendering of the Enterprise. Source: Lloyd, James T. (1856), Lloyd’s steamboat directory, and disasters on the western waters… , Philadelphia: Jasper Harding.

Today, river cruise companies such as American Cruise Lines and American Queen Steamboat Company operate stern-wheelers on the Mississippi and Ohio (as well as other rivers). Their stern-wheelers were inspired by another steamboat named Washington, which was launched in 1816 as the first steamboat featuring two decks. By the 1830s, the age of the stern-wheeler was booming, with more than 1,200 in operations..

Along with the stern-wheeler, showboats made their debuts. These were floating theaters designed to accommodate passengers rather than cargo. The early showboats had to be pushed by towboats because the auditorium occupied that space that a steam engine would require. In 1816, the American actor and theater manager Noah Ludlow launched the first showboat when he purchased a flat-bottomed keelboat for $200 and named it Noah’s Ark. Ludlow formed the American Theatrical Commonwealth Company and traveled in Noah’s Ark along the Ohio and Mississippi for performances to the widely scattered audiences along the rivers.

One of the most important events to propel steamboats forward, however, was not a boat or a river. It was Mark Twain’s 1883 book “Life On The Mississippi.” Today, Twain’s tales still inspire people worldwide to go on – or aspire to – Mississippi River cruises on modern-day paddle-wheelers that are a mix of showboat and steamboat. To take a peek inside one of these boats and the Mississippi River cruise experience, check out the series of videos that we produced featuring American Queen.

Built in 1995, the American Queen is a stern-wheeler. © 2012 Ralph Grizzle

Meanwhile, In Europe

While stern-wheelers were growing in popularity in America, side-wheelers were churning up the rivers in Europe. The side-wheelers were inspired by the inventor whose name appears many times in these writings, Claude Dorothée Marquis de Jouffroy d’Abbans’. A few decades following de Jouffroy’s successful sailing on the Saône, river tourism on side-paddle wheelers began to emerge. Nowhere was the trend more popular than in Germany.

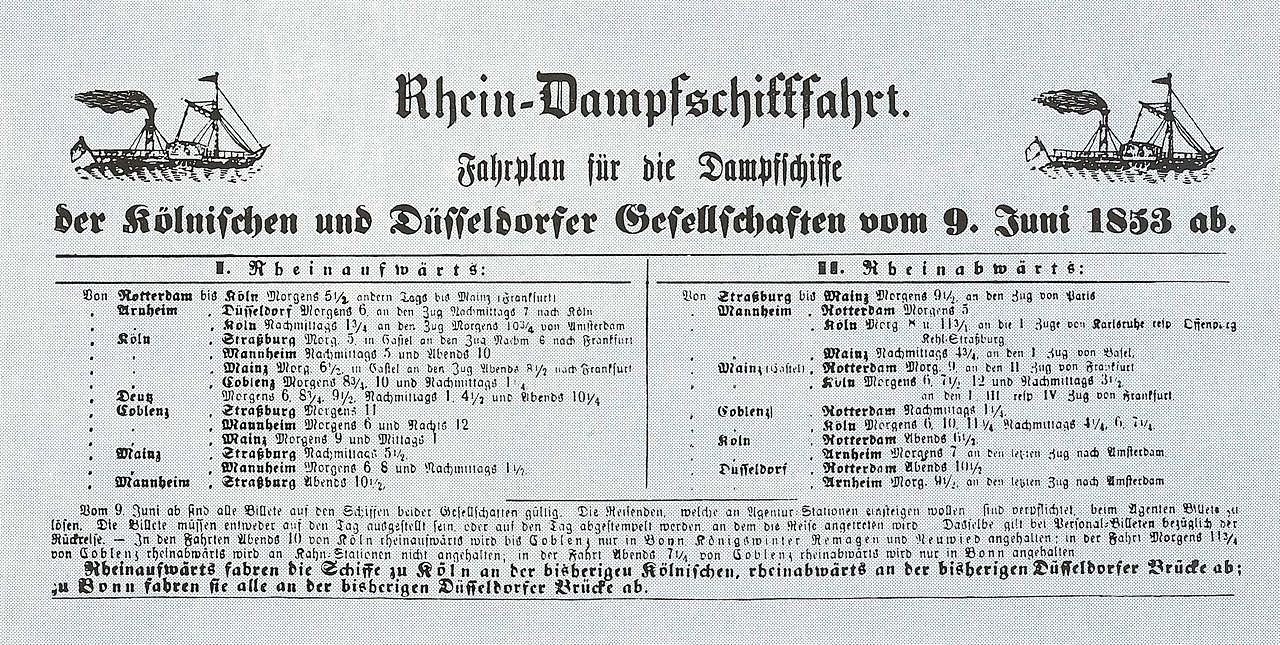

In 1827, the newly formed Prussian-Rhenish Steamship Company (PRDG) began operating passenger and freight services between Mainz and Cologne. With business going well, PRDG launched a second steamer into service during the summer of the same year. Fast forward to the fall of 1836 when merchants from Mainz, Germany formed the Steamship Company for the Lower and Middle Rhine (DGNM), based in Düsseldorf. DGNM had put five steamers into operation by 1838.

After nearly two decades of competing against one another, PRDG and DGNM founded the operating group Kölnische und Düsseldorfer Gesellschaft für Rhein-Dampfschiffahrt (Cologne and Düsseldorf Society for Rhine Steam Shipping). Suffice it to say that the Germans seem to appreciate long names for companies. The operating group later would become known as KD Steamer Line, the K representing the Cologne (Köln) company (PRDG), and the D representing the Düsseldorf company (DGNM).

Rhine timetable for 1953 Betriebsgemeinschaft Kölnische und Düsseldorfer Gesellschaft für Rhein-Dampfschiffahrt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1860, the two companies, which each owned 14 steamers, carried 1.2 million passengers. The voyages were not the weeklong journeys that we enjoy on river cruises today. Rather they primarily were sightseeing trips between Dusseldorf, Cologne and Mainz. The route passed through the famed Rhine Gorge and the landmark high rock known as the Lorelei.

It’s worth taking a moment to talk about the Lorelei, which you’ll still pass during the daylight hours on many Rhine cruises today. The Lorelei became a famous day outing following a poem penned by Heinrich Heine in 1824. Heine was inspired by a story about a beautiful woman betrayed by her lover, who accused her of bewitching men to their deaths. For her alleged crimes, she was sentenced to serve the remainder of her life in a nunnery.

On the way to the nunnery, she asked the three knights accompanying her if she could climb the Lorelei for one last look at her beloved Rhine. Gazing into the river, she thought she saw the lover who betrayed her and fell to her death. Her haunting story still echoes in the rock and the river below. In “Die Lorelei,” Heine depicted “the fairest of maidens … sitting up there … combing her golden hair,” luring seamen to their deaths with her spellbinding song.

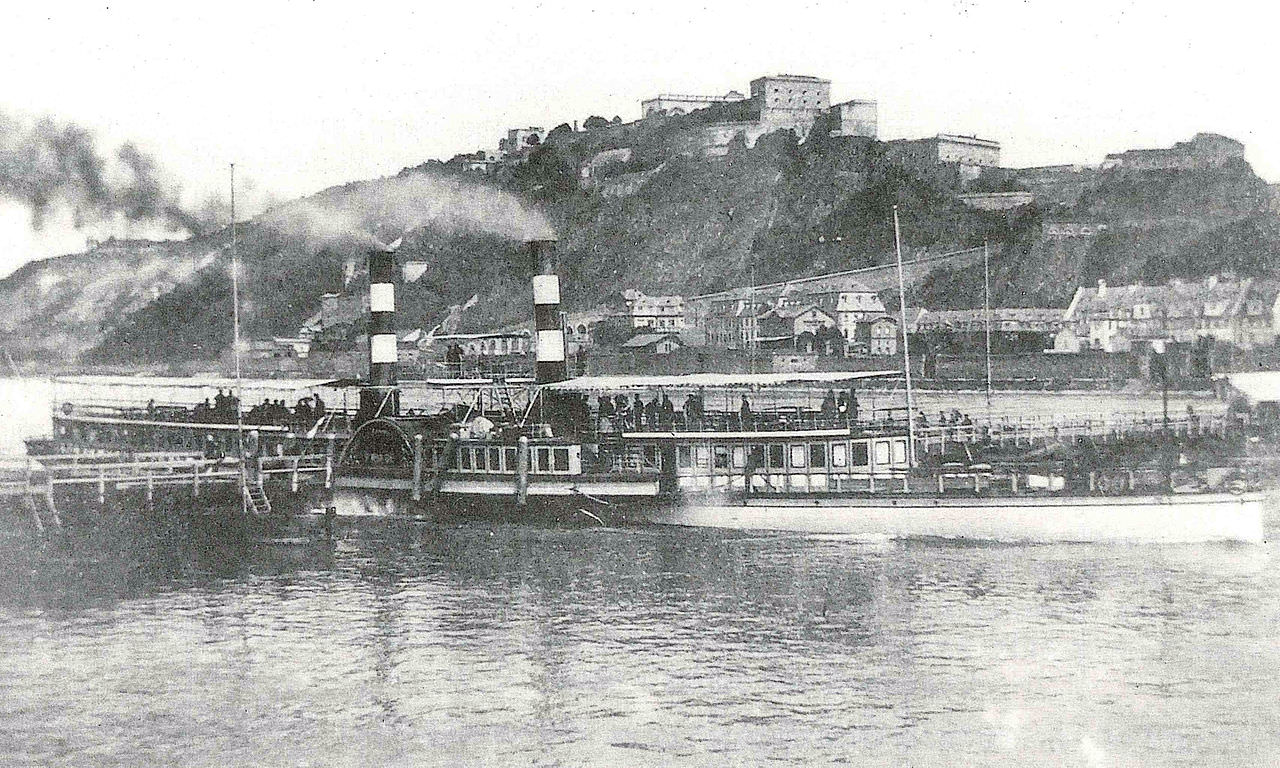

A steamboat passes the Lorelei in Germany, ca. 1900 Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Lorelei is the most famous feature along the Rhine Gorge, which runs between Koblenz and Bingen, a distance on the river of about 40 miles. For more than a century, the gorge has been a popular river outing. During the mid-1800s, sightseeing cruises became increasingly important for revenues as cargo increasingly shifted to the newly developing railway systems throughout Germany.

One of two boats built for passengers only, the paddle steamer Friede on the Rhine River in Koblenz, Germany.

In 1867, KD put into service the first two boats for passengers only. Each of the two companies began launching two new ships into service annually so that by 1914, the operating group had 32 ships carrying more than 1.9 million passengers annually. At about the same time, the last smooth-deck steamer went into service for combined freight and passenger traffic. The name of the steamer, Goethe, which we’ll hear more about in a moment.

During World War I, some of KD’s steamboats were converted to hospital ships. Others were used to transport troops. After the war, business resumed as the “Roaring Twenties” ushered in the need for luxuriously equipped passenger boats. In 1928, a third company joined KD with 10 steamers. That same year, the company put the last paddle-steamer into service. KD was now carrying more than 2.5 million passengers annually, but the global economic crisis of the 30s saw passengers fall by more than 20 percent and freight transport by 50 percent.

Worsening matters, World War II saw the loss of many of historic boats. Goethe was bombed and spent several years submerged on the Rhine river bed. The steamboat was resurrected and returned to service in the early 1950s. By 1953, 18 ships had been repaired, including 14 paddle steamers.

Up until this point in our story, none of KD’s vessels could accommodate passengers for overnight voyages along the Rhine. There were no cabins for passengers to sleep, and thus, river cruising as we know it today remained elusive. That all changed in 1960 when KD launched Europa. Built with cabins for up to 150 passengers, Europa operated on the Rhine between Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, and Basel, Switzerland.

Europa continued to operate Rhine cruises until 1995, but KD increasingly faced operational challenges. The company had to contend with cheap charter trips abroad and an increase in automobile tourism. Plus there were competitors on the rivers, which we’ll learn about later. Operating at a loss, KD split its river cruise business and day-trip business, selling the river cruise business to Viking River Cruises in 2000 and the day-trip business to Premicon.

Viking’s purchase of KD’s river cruise business was significant, as it gave Viking access to KD’s long-established and extensive network of docks along the Rhine and other rivers throughout Europe. The purchase also made Viking River Cruises the largest river-cruise operator in Europe, with 26 river vessels and two ocean-going ships.

In 2008, the history of steam navigation on the Rhine came to an end when KD converted the paddle-steamer Goethe to diesel. Goethe continues to operate and remains as KD’s last example of paddle propulsion, offering day trips along the Rhine. But with its conversion to diesel, the age of the steam engine, which had launched river cruising, had become a historical footnote. Goethe’s engine was put on exhibition at the Cologne City Museum.

The paddle-steamer Goethe, pictured here in 1975, was the last of its kind to operate on the Rhine. Goethe’s steam engine was converted to diesel hydraulic in 2008/2009. The ship still operates for K.D. Line today. Photo courtesy Lothar Spurzem, CC BY-SA 2.0 DE, via Wikimedia Commons

From the first sailing on the Saône in 1783 through the 1960s, steam engines were the driving force behind the evolution of river cruising. Steam eventually gave way to diesel, and vessels shifted from carrying cargo to carrying passengers, from day trips to overnight voyages. With 75 cabins for overnight journeys, the diesel-powered Europa laid the groundwork for the future of river cruising. But while Europa was the first of its kind on the Rhine, it was not the first vessel to feature cabins on the waterways of Europe.

In our next two posts, we’ll leave Germany and the Rhine. We’ll first head to France to board vessels that were designed to carry cargo but were converted to hotel barges to transport passengers on scenic journeys through Burgundy. After that, we’ll head to a country not often associated with river or canal trips to learn about the world’s oldest passenger ship. It still operates today, crossing Sweden.

For The Nostalgic: Paddle-Wheelin’ & Steamboatin’ Today In Europe

At about the same time that KD was evolving, Weiser Flotte Sachsen was developing its fleet in Dresden. Known as the “White Fleet,” today the company boasts the world’s oldest and biggest fleet of paddle-steamers. At the turn of the last century, the company operated 37 ships with a capacity for carrying 23,000 people. In 1901, the White Fleet transported more than 3 million people.

The White Fleet’s Bohemia docked at the pier in the Italian village. In the background: the Semper Opera House. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The company that now owns the White Fleet, the Saxon Steamboat Company, continues to operate nine historic boats, which carry around 700,000 passengers annually. The steamboats travel the Elbe between Diesbar-Seusslitz and Bad Schandau, and occasionally as far as Ústí nad Labem in the Czech Republic. During the season, the steamboats paddle past the Elbe’s inspiring landscape, dotted with castles and vineyards.

Those who prefer one-week or longer paddle-wheel voyages on the Elbe can turn to CroisiEurope. The Strasbourg-based company operates two stern-wheelers. The Elbe Princesse I and II operate nine-day voyages between Prague and Berlin.

CroisiEurope’s stern-wheeler MS Elbe Princesse II. Courtesy of CroisiEurope

CroisiEurope also operates on France’s Loire River, with the side-paddle wheeler Loire Princesse. The paddle wheelers on the Elbe and the Loire allow the boats to navigate those rivers’ notoriously shallow waters. Read more about these paddle wheelers in our voyage reports, Loire Princesse and Elbe Princesse.

My husband and I took a day trip on a KD boat in 1998. This would be our first and only venture on the Rhine until 2016. It was a fun sail, and you were allowed to get on and off at various stops if you wanted. We were in Alsace Lorraine for a 5 week study abroad. In those days, we had rail passes that would take you all over Europe. Every Thursday I took my students on an educational field trip, and then students and teacher headed out in various directions – no class until Monday. One week-end we took our Rhine sail which involved some planning and train travel. We stayed overnight in Koblenz and boarded the KD boat in the morning.