Just outside Dijon, in the heart of Burgundy’s wine country, I spent a morning learning about the age-old craft of cooperage—the shaping, bending and binding of oak into barrels. I was invited to Burgundy to review AmaWaterways‘ Flavors of Burgundy river cruise and its excursions.

Our ship, AmaCello, was docked in tiny Seurre, a quiet riverside town on the Saône that once served as a strategic port for river trade. We traveled by motorcoach for about 30 minutes to reach Art du Tonneau, where we’d all walk away with a whole new appreciation for an object many of us had rarely thought about.

We not only watched a master cooper at work—we also took part in assembling a barrel ourselves. We helped fit staves, position hoops and witnessed firsthand how heat and skill turn raw oak into something that holds both wine and more than two millennia of history.

Barrels: Born Of Battle & Built To Last

Before we touched a single stave, Daniel—our informative, engaged and genuinely funny host—began with a story. Wooden barrels, he explained, date back more than 2,000 years. It was the Celts who invented the barrel—developing a container made of wooden staves and hoops that was durable, watertight and easy to transport. When the Romans expanded into Celtic territory, they quickly adopted the barrel for wine, oil and military supply transport, replacing their traditional clay amphorae. A single person could roll a full barrel with ease, making it ideal for trade and conquest alike.

Inside The Cooper’s Workshop

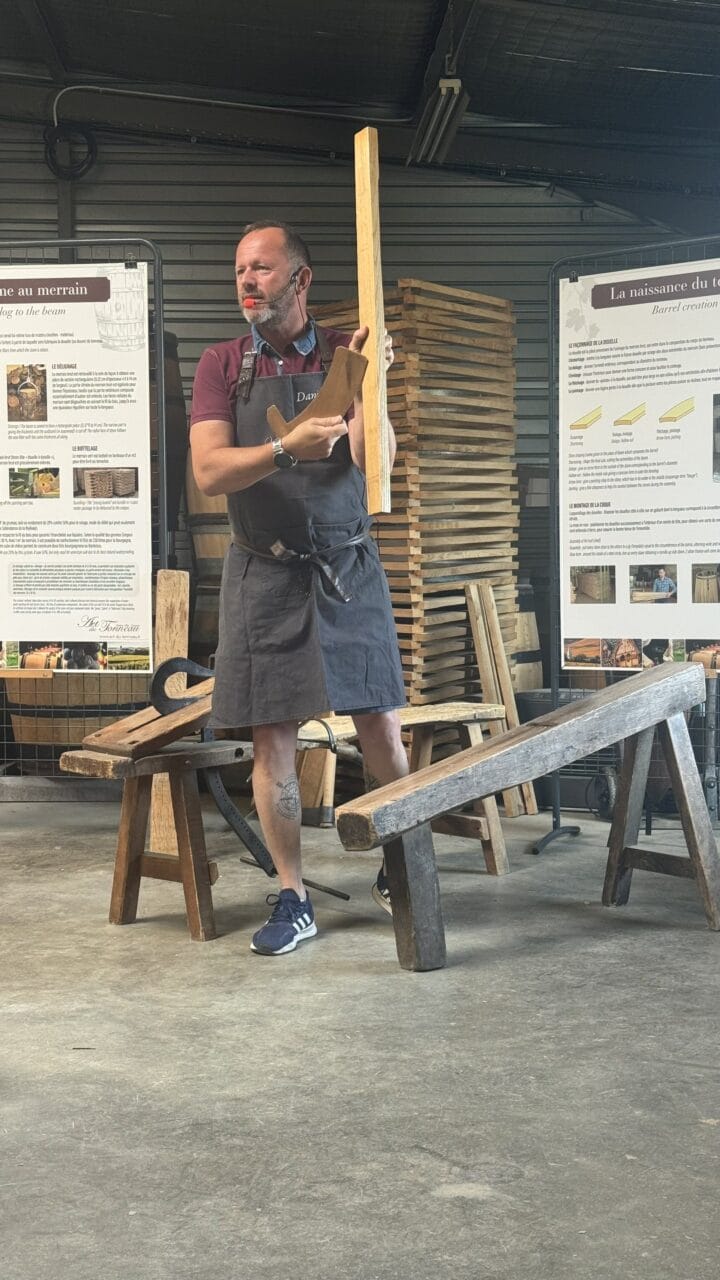

The workshop at Art du Tonneau is filled with the scent of oak, long staves, iron hoops and well-worn hand tools resting on benches polished by decades of use.

Daniel began by showing us long, narrow pieces of French oak staves, which had been seasoned for two years. These staves—the curved wooden slats that form the sides of the barrel—are planed and shaped using traditional tools so that, when joined edge-to-edge, they’ll form a seamless, watertight cylinder—no glue, no nails.

Every movement is guided more by feel than by measurement, each stave carefully fitted into place. The result is a “rose” of oak slats, held together by a temporary hoop—a skeleton of a barrel, ready to be brought to life.

We split into groups of five to do what Daniel had done with only a single assistant. It was challenging for us to put together a barrel, something that Daniel could do in six minutes. After 15 minutes, we were still at it. The competition was fierce and spirited. After all groups had finished their barrels, Daniel went around an inspection. “Not bad,” he said of one as he rolled the barrel on its edges. “This one is for IKEA,” he said as the barrel’s flimsy staves squeaked while being rolled. Our barrel? We performed as master coopers, and I am proud to say that our group won best barrel.

Fire & Flavor: The Art Of Toasting

Our job was not finished, but our work for the day was over. I found it interesting, however, to learn about the rest of the process. The half-formed barrel is placed over a brazier. As flames warm the inside, the oak begins to bend. Though there were no actual flames during our demonstration, Daniel showed us how to tighten the hoops, gently shaping the barrel into its familiar form.

This is where the real alchemy begins. Toasting the inside of the barrel doesn’t just soften the wood—it releases flavor. French oak, especially from forests like Tronçais, Allier and Nevers, is prized for its tight grain and high tannin content.

When gently toasted over fire:

- Lignin breaks down into vanillin, releasing warm vanilla aromas

- Hemicellulose caramelizes, producing sweet, nutty, toasty notes

- Deeper toast levels evoke mocha, spice, smoke—even chocolate

Daniel explained the different toasting levels.

- Light toast emphasizes structure and spice

- Medium toast brings out vanilla and caramel

- Medium-plus adds mocha and roasted nuts

- Heavy toast leans into char, smoke, and bold intensity

A Barrel 200 Years In The Making

Daniel told us that often the trees used in barrel-making are 200 years old—a result of meticulous forest stewardship going back to the reign of King Louis XIV. In 1669, his finance minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, issued the Ordonnance des Eaux et Forêts, a sweeping policy that laid the foundation for sustainable forestry in France. His goals were military—he wanted strong oak for warships—but his methods endure today:

- Long harvesting cycles of up to 250 years

- Selective cutting and replanting

- Managed forest inventories

Thanks to Colbert, France still has some of the finest oak forests in the world, and its cooperage tradition thrives—not in spite of conservation, but because of it.

The Afterlife Of A Barrel: Portugal, Scotland & Beyond

What happens after the wine is bottled? Most French barrels are exported, especially to North America, where California vintners are major buyers.

Used French barrels are rarely discarded. Instead, they travel:

- Many are sent to Portugal, where they’re used to age Port, Madeira, and tawny wines

- Others go north to Scotland, where distillers use them to finish single malt whiskies

The wine-seasoned oak imparts subtle fruit and spice to the spirit. Even after their aging life ends, barrels are reborn—into planters, furniture or décor. The wood holds its character long after the last drop has been poured.

More Than A Container: A Vessel Of Time And Terroir

I learned that barrels are more than a vessel to vinify wine. They hold the age of a forest, the knowledge of a craftsman, the transformation of fire and the patience of wine at rest. From the moment the tree is selected to the final bottling, a barrel participates in a story that spans centuries.

While machines have largely replaced coopers for mass-market barrel production, traditional coopering is still very much alive in premium winemaking, especially in France. Automated systems can produce hundreds of barrels per day, but a traditional cooper might finish just one to three barrels depending on the complexity and finish. Coopering is truly an art form.

Thanks to Daniel’s passion and AmaWaterways’ thoughtful inclusion of this wonderful experience, my morning while our ship was docked in Seurre became one of the most unexpectedly enriching parts of my time in Burgundy—just as Simon promised it would be.

2 Responses

Bonjour Monsieur

Merci pour votre article. Je suis vraiment très heureux d avoir participé a la réussite de votre sejour en Bourgogne

Avec toute ma sympathie.

Daniel.

Thanks Ralph for this very informative explanation of your tour; if I ever sail the Saone/in Burgundy, I will inquire about taking the tour.